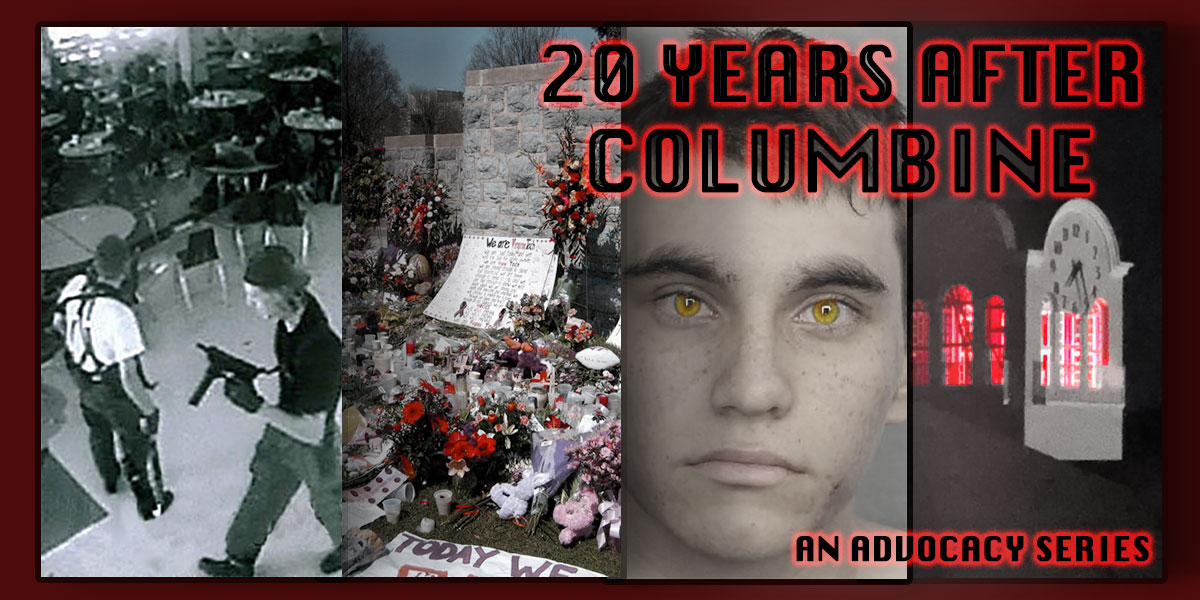

— Part 1 of an 8-Part Series —

April 20, 2019, marks the 20th anniversary of the Columbine High School mass shooting, which was ranked the worst school shooting in U.S. history until the Stoneman Douglas High School shooting on Feb. 4, 2018, and was one of the deadliest episodes of school violence. Today’s story is the first in an 8-story series, and we are posting it at 12:19 p.m. local time (11:19 a.m. Mountain Time), which is exactly when two Colorado students walked into their high school two decades ago and began a killing spree that left 13 dead, before killing themselves, permanently altering our sense of security in schools.

_________________________________________________

As we arrive at the 20th anniversary of the shooting today, the deadliest attack at a U.S. high school in history until the Stoneman Douglas High shooting in Florida last year, MBU Timeline staff journalists decided to compile an advocacy journalism series, in which we’ve explored the topic of active shooters, specifically in schools and universities, and reported on various related topics. After the Columbine shooting, a new standard procedure for law enforcement was put into place. Steve Heidke, director of public safety at MBU and police officer since 1977, said the whole mentality of law enforcement changed. The plan of action during Columbine was to surround the building and contain the issue of the shooter, however, law enforcement found this only adds to the body count because the shooter is left inside to finish their intended duty. Before Columbine, law enforcement looked at mass shootings as hostage situations. Police would surround the building and try to talk the shooter into giving up on their mission, but this 1999 protocol failed, and 13 people were killed. After additional information learned through the 2007 Virginia Tech shooting, ranked as the deadliest shooting rampage in U.S. history, according to Ranker, the new standard procedure is for law enforcement to enter the building upon arrival and neutralize the shooter. Heidke said after Columbine, “they started training officers to go in and neutralize the shooter. The whole mentality of law enforcement changed after Columbine. They discovered that all this (previous protocol) meant was that he had more time to kill people.” On the Virginia Tech campus in Blacksburg, Virginia, on April 16, 2007, 23-year-old senior English major, Seung-Hui Cho, killed 32 people and then took his own life. After the Virginia Tech shooting, the U.S. Department of Education made changes to the Campus Crime Act, requiring that each campus nationwide has two types of emergency campus notifications. At MBU, emergency call buttons, campus-wide emergency alert systems, emergency notifications and timely warnings were all implemented. “Virginia Tech changed everything for college campuses, it started emergency notifications and timely warnings … that’s what mandated us putting in campus alert systems and call buttons all over campus,” Heidke said. In considering the horrific possibility of a shooting at MBU, Hedike said students and Public Safety are unable to predict or perfectly plan for an active shooter. “That’s the whole part about an active shooter, there’s no way to predict it. We are ready to deal with it, but we can’t predict it,” Heidke said. Campus security covers every shift, 24/7, he added, but MBU Public Safety currently has 10 working officers with 14 positions available. Heidke said there are days when the department could use more help, and they have trouble hiring officers because of their lower pay compared to surrounding municipalities. Each public safety officer is certified through the state of Missouri and has the same certificate of Creve Coeur and St. Louis County police officers, and they are all pro-certified police officers, which means they have completed the proper training. In the event that a suspicious person would be seen on campus, Public Safety relies on faculty and staff members to identify them and notify Public Safety because two armed officers can be dispatched to that location in a matter of minutes. “We are relying on training the instructors,” Heidke said. MBU faculty and staff members participated in a four-hour active shooter training Feb. 20, where Creve Coeur police officers led faculty and staff members through the steps of what a real active shooting case could be like. But Heidke pointed out this training pertains to faculty and staff members only, not to MBU students. “The only problem with training students on active shooters is most active shooters are students, and we don’t want to give some student the manifesto on how to defeat our system,” Heidke said. Public Safety shares limited information and procedures with students “to prevent students who may revolt,” Heidke said. One of the only published sets of steps for an active shooter scenario is posted inside each classroom door. Other than a few basic instructions, Hedike said, it’s up to individual instructors to lead students to safety. Other campus safety information can be found on the MBU website. Classroom doors are specifically designed for the event of an intruder, as each door can be locked from the inside and only unlocked from the outside by Public Safety officers and a few administrators. With the largest gathering place on campus being the Dale Williams Fine Arts Center and Pillsbury Chapel, two or three armed officers are always on location before the students arrive. Once the Chapel doors are closed and locked for the duration of Chapel, Public Safety officers stand right inside each entrance. Each NAIA-sanctioned event has at least one armed officer at every game. Just like in Chapel, Public Safety will act accordingly to their training, in the event of a shooter, and wait until further help arrives. Starting on the first day of classes in fall 2019, instructors will review emergency procedures with their students when taking attendance and going over their syllabi. In the case of an active shooter on campus, students are advised to do the following: Every summer, MBU Public Safety brings in both Creve Coeur and Town and Country police departments for classroom active shooter training, and each Christmas break the three departments perform these drills in the dorms. The purpose is to train MBU Public Safety to work with Creve Coeur and Town and Country officers in case of an incident.