It has been over a month since millions of people across the United States received the first-ever Presidential Alert as a text message sent to their phones, and people find themselves still asking the question, “What does this mean for the future of government alerts, and how will they affect me?”

Copyright-free photo from Google images

_______________________________________________________________

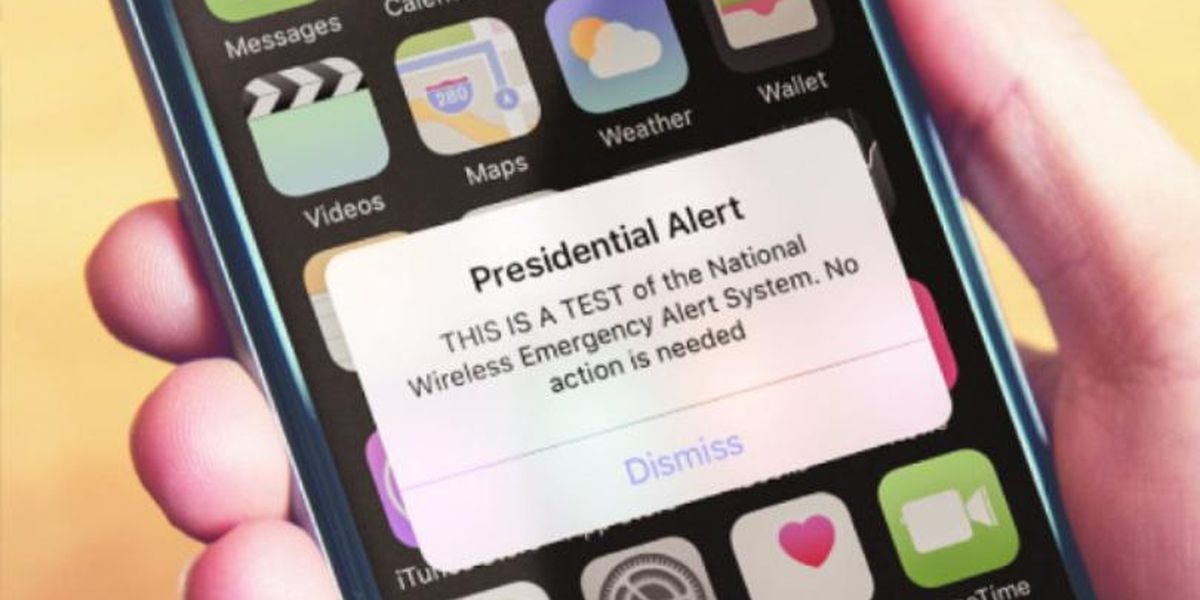

“THIS IS A TEST of the National Wireless Emergency Alert System. No Action is needed,” read the message sent out by the Federal Emergency Management Agency. Nearly 225 million people nationwide received this Wireless Emergency Alert, which was sent out across all carriers, such as AT&T, Sprint and T-Mobile. Some smartphone users did not receive this message, but the ones who did were unable to block the alert from their phones. FEMA created the WEA system in 2016 as a way to alert the public of terror attacks and other disasters, so even though the message is called a Presidential Alert, it is unlikely that President Trump will send one out himself. The alert was originally supposed to be sent out on Sept. 20, but was postponed until October due to the hurricanes that caused damage to the southeast part of the country at the beginning of the month. Presidential Alerts are broadcast across radio and television platforms in unison with the text messages, so people who do not own smartphones are able to receive the alerts as well. National radio and television broadcast alerts are not a new form of reaching the public. These types of alerts have been used since the mid-1900s to alert citizens of danger and disaster. “I always get the amber alerts and they don’t bother me. They’re a little noisy but they’re helping someone so that’s all that matters. Same with the new Presidential Alert, it’s just going to help us in the long run,” said Brandon Whitehead, 31. News of the presidential text message went viral on social media the day they arrived on U.S. citizens’ cell phones. The topic was trending on Twitter with some people praising the message and others upset by the fact it can’t be blocked. “I never received a message, so it doesn’t really affect me at this point in time. I feel like the messages should be able to be turned off like Amber Alerts though. Some people at my work were getting the alert over and over again even though it was just a test,” said Lindenwood University senior anthropology major Paige Walsh, 22. Another college student, Katelyn Gronemeier, 21, of St. Charles Community College, said, “I didn’t mind the alert. I get Amber Alerts and the weather reports sent to my phone. I like to know if I need to be prepared for an emergency or not.” Some people believe the current president and future presidents could use this messaging system for personal use, but there are laws intact to prevent this from happening. The Integrated Public Alert and Warning System Modernization Act of 2015 states,“Except to the extent necessary for testing the public alert and warning system, the public alert and warning system shall not be used to transmit a message that does not relate to a natural disaster, act of terrorism, or other man-made disaster or threat to public safety.” State governments have their own Emergency Management Agencies in addition to FEMA. The Hawaii Emergency Management Agency caused public disturbance in January when an emergency alert warned the state of a missile threat and told people to seek shelter. Turns out the message was sent by accident and there was no threat. Due to the public scare, FEMA uses the text messaging system to check for bugs and other issues with the WEA. The federal agency believes testing can prevent another crisis such as this one from occurring again.