After prematurely closing in spring 2020, schools were back in session in the fall, but many were missing a familiar component of classrooms: student teachers and observers. As individual school districts decide whether or not to allow outside individuals into their buildings, the MBU School of Education is working through the challenges coronavirus has presented to their students to give them the in-person experience they need.

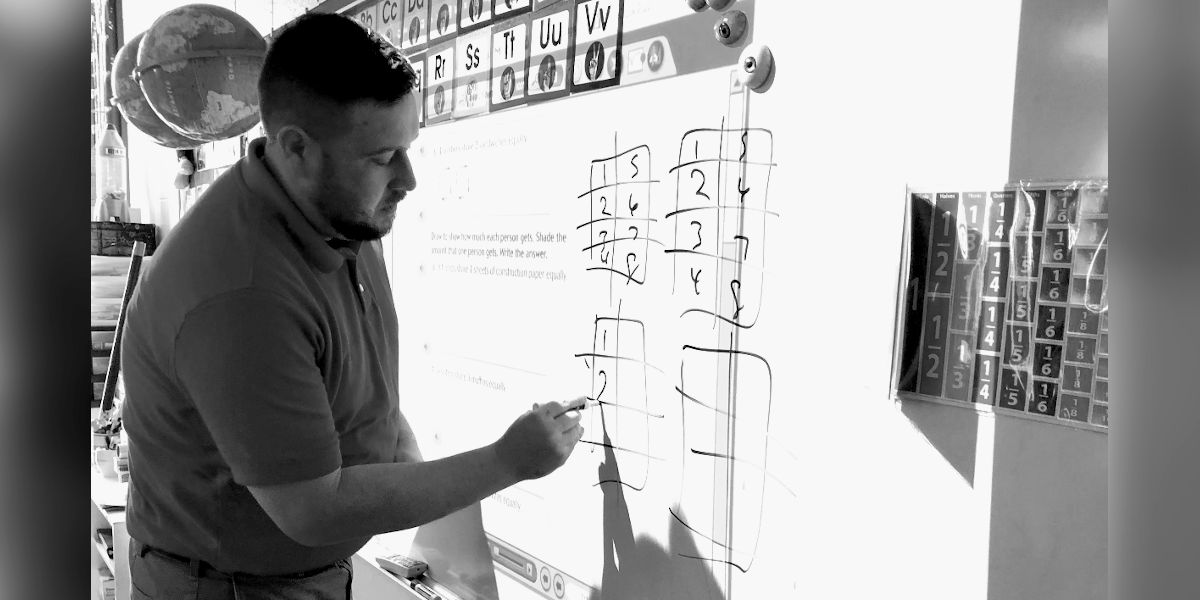

The ability for School of Education students to get face-to-face interaction with children in St. Louis area schools has been made more difficult, but not impossible, as districts try to comply with coronavirus restrictions. Photo courtesy of MBU School of Education

The ability for School of Education students to get face-to-face interaction with children in St. Louis area schools has been made more difficult, but not impossible, as districts try to comply with coronavirus restrictions. Photo courtesy of MBU School of Education

__________________________________________________

With children returning to classrooms in fall 2020, St. Louis and its neighboring counties implemented protocols and regulations with varying degrees of severity to help ensure the safety of students attending school in person. As districts tried to achieve a sense of stability and prevent spikes in coronavirus cases, non-essential staff and visitors were often barred from entering schools, which included prospective educators needing first-person experience in classrooms. Phil Ragusky, director of field placement for the School of Education, said there are many factors to weigh at the moment when placing students in classrooms, and reaching a solution that works for all parties involved can be difficult. “As you can imagine, we have a variety of placement options and challenges. The biggest is that several larger schools that we typically use are virtual or not allowing visitors in their schools. Others are limiting access for such things as student teaching but are allowing field students. Still others are just the opposite,” Ragusky, who assumed his position in October 2020, said in an email. “It is a juggling act to place students relatively close to their first choice schools, not over-tax schools that are allowing access to us and, finally, meeting the protocols of all the different districts. We have tight restrictions in St. Louis County and less restrictive in St. Charles, Franklin and Jefferson counties.” According to Ragusky, field experiences, like Field I, are when students wanting to become certified teachers observe, teach lessons and engage with students in local K-12 schools. A pair of field experience courses and student teaching are necessary to fulfill this portion of students’ degree requirements. Field experience I requires the student to teach one lesson with 30 observation hours, field experience II requires the student to teach two lessons with 45 observation hours, and student teaching usually consists of the student attending their placement school daily for 16 weeks while teaching lessons and engaging students as the regular teacher. Kendra Ray, administrative coordinator for teacher education and director of folio in the School of Education, pointed out the combination of an increased number of MBU students needing placement and limited number of locations accepting students has made the process even more competitive. “There are a number of districts who we typically rely heavily on that are not currently letting us in – either because they are still virtual or because their visitor policy does not allow for field experience students,” Ray, also an adjunct instructor, said in an email. “In addition, a number of students who were initially planning to take Field I last semester were delayed until this semester in hopes of things being more ‘normal.’ So the number of students we need to find placements for this semester is much higher than normal … and yet, we are still working with a limited pool of schools willing to host.” According to Ray, some Missouri districts like Mehlville, Orchard Farm, Washington and Gateway Science Academy are now hosting MBU students; however, districts like St. Charles and Parkway are not allowing MBU students for the second semester in a row, which has created a challenge for main campus students because the School of Education normally relies heavily on those districts. The situation has improved from the fall 2020 semester, however, when most schools across the St. Louis region were not allowing any non-essential personnel inside their buildings, resulting in many students delaying their observation and student teaching until the spring 2021 semester. Madison Oellermann, who is doing field experience with the fourth grade at Orchard Farm Elementary School in St. Charles, Missouri, had to delay her plans to complete her observation hours by a semester. “I think we were really supposed to do it last semester, but we didn’t, so then we just did the paperwork in the fall and it got pushed until spring. I got my placement before the semester started, which I think was unusual. I think most people didn’t,” said Oellermann, a sophomore elementary education major from St. Charles. Dorian Jett, who is placed at Gateway Science Academy in St. Louis, shares similar experiences with Oellermann on finally being able to get inside classrooms despite COVID-19 protocols. “Placement was a little different this year. My observations got pushed back a semester due to limited school options. They were still pretty limited this semester because a lot of schools are not taking extra visitors,” Jett, a sophomore special education major from O’Fallon, Missouri, said in an email. “I got the chance to listen to the principal of Gateway Science Academy speak in one of my classes, and luckily her school ended up being on the list to choose from. I got placed at that school and get to observe a variety of grade levels while still having a home room teacher.” Although some avenues for students have closed because of coronavirus, others have opened due to Ragusky’s previous position as director of human resources at Parkway Schools as he has begun cultivating potential relationships between local districts and MBU. “I have connections across the counties where we place students and, in some cases, my connections are at districts that were at times previously untapped. Additionally, I am working on creating and nurturing partnerships that will help us bridge such limitations (in the future) with districts that agree to work directly or hopefully exclusively with MBU,” Ragusky said. In spite of the challenges, the MBU School of Education is still having success placing students for in-person observation and teaching, which Ragusky said is preferential over virtual options. “Not only is the in-person important, we have taken the stance that unless there are no schools with in-person options, we will avoid virtual-only options. There is nothing quite like being able to engage with students in-person, no matter how great the virtual situation,” Ragusky said. Regardless of where students are placed for their field experience, the COVID-19 pandemic has changed the way classrooms are currently operating, and there are varying guidelines, protocols and restrictions each district has put in place or must abide by. In the Mehlville school district, student observers and student teachers must complete a screening before they can enter any of the buildings, and if they can answer “yes” to any of the questions, they must remain off campus and alert their supervisor. Jessica Pupillo, director of communications at Mehlville, said safety protocols are in place to keep students safe, including masks and plexiglass, as well as a robust contact tracing process. “While on campus, everyone must be masked. And we work to allow social distancing whenever possible. Our elementary schools recently returned to full attendance (what we call Plan A) and it’s not always possible to maintain 6 feet of distance throughout the day. In those instances, we try to keep students clustered in pods or provide physical barriers like plexiglass,” Pupillo said in an email. Alaura Dalgetty, who is completing field experience for kindergarten at Hillsboro Primary School in Hillsboro, Missouri, said she must complete a temperature check and a screening each morning she goes to the school, and the children are more separate than normal. “My cooperating teacher explained to me how typically she’s more of a collaborative type of teacher … but with COVID, they have to stick to their specific table, they have dividers in between each section of the table, and then there’s contact tracing so if someone at the table has been exposed then the whole table could have been exposed, so the whole table has to go into quarantine. So they’re very diligent with that,” said Dalgetty, a junior elementary education major from De Soto, Missouri. Some schools are also implementing a hybrid model, such as at Gateway Science Academy South where Haleigh Webber, a sophomore majoring in special education and elementary education, was placed. “GSA is hybrid right now, so half of the student body attends school in-person part of the week and is online the other days, and then they switch with the other half,” Webber, an O’Fallon, Missouri, native, said in an email. “The students who are in-person sit in class on Zoom with the other students and the teacher sits at her desk and teaches over Zoom. That was definitely not what I was expecting to see, but it has been interesting to see how the teachers have adapted to hybrid learning.” Oellermann said Orchard Farm Elementary only recently returned fully to in-person learning after having their entire previous semester held online, so the children in the class were adjusting as well. “So, her class, the teacher that I got put with, her entire semester last semester was online, so they were all virtual, and so when I came in the first time it was like their second day in school, so it’s hard for them to sit still because they’ve been at a computer all the time doing whatever they want,” Oellermann said. “I think the teacher is having a lot of trouble with their grades and stuff, but I don’t know. It’s interesting to see the ramifications of virtual.” In addition to acclimating to the way they are learning, the children have to adapt to the way they may now socially interact with each other. “You can tell them a million times not to touch each other, not to touch you, to keep their masks on, but they’re little kids. They’re gonna take their masks off, they’re going to have to be reminded to keep them on,” Dalgetty said. “They’re going to be reminded several times a day not to hug each other, not to touch each other or borrow each other’s things. It’s really hard for them not to hug you because that’s something that they just do and they do it out of habit almost.” Looking for silver linings, Dalgetty said there are some lessons in sanitation that can be implemented in the future to help with the seasonal flu and other diseases, which schools are hotbeds for. “I think it really makes us aware of spreading disease and making sure we’re keeping clean, and it’s a really big lesson for those little kids because they don’t understand germs. They don’t understand that they spread so easily, and especially with those younger kids,” Dalgetty said. “It’s a lesson on adapting to the situation.” Although COVID-19 has placed unforeseen obstacles before MBU School of Education students, Ray said they have been able to find creative, workable solutions. “While our options have been limited this semester, we are getting many students placed. It’s just taking a lot of time and more ingenuity,” Ray said.