“The Imitation Game” is less of a tragedy than a celebration of Alan Turing’s work life. An individual who has shown us heroically that “sometimes it is the people whom no one imagines anything of who do the things that no one can imagine.”

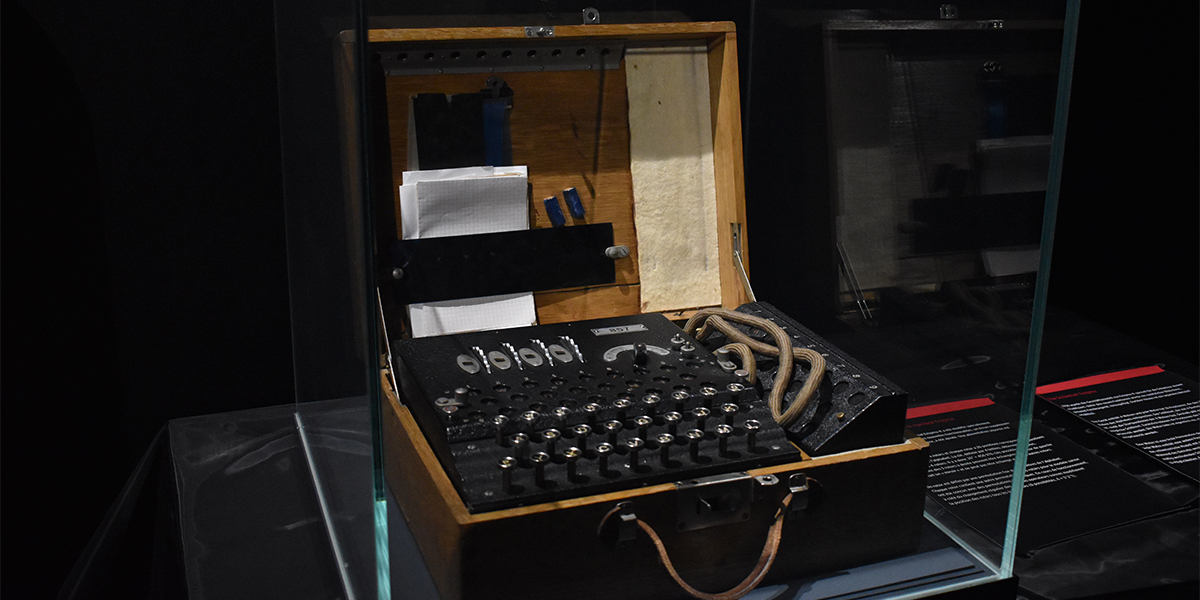

An encoding machine, similar to the Enigma used by the Germans for all communication in World War II, proved to be one of the Allies’ greatest challenges, as portrayed brilliantly and with historic accuracy in Mortem Tyldum’s film. Photo by Mauro Sbicego

An encoding machine, similar to the Enigma used by the Germans for all communication in World War II, proved to be one of the Allies’ greatest challenges, as portrayed brilliantly and with historic accuracy in Mortem Tyldum’s film. Photo by Mauro Sbicego

__________________________________________________

The drama of Mortem Tyldum, which is that of a war hero, begins extremely nervous, yet captivating. The war hero who saved 14 million lives and shortened World War II by two years. The same war hero who had to undergo hormone therapy after the war due to “gross indecency,” and the same war hero who died at the age of 41. Only in 2013 did Queen Elizabeth II grant Turing a posthumous Royal Pardon, honoring his unprecedented achievements during the war. In 1939, after England had declared war on the Germans, a young man defined by arrogance and social incompetence applies to the Government Code and Cypher School. With four other brilliant minds, he is tasked with beating the daily changing German Enigma, a to-that-date unbeatable communication encryption machine. Alan Turing, not very enthusiastic about working in joined forces, realizes early on that only an automatic calculating device can be fast enough to filter out one of the 150 trillion — as in 150,000,000,000,000 — possible combinations in a short enough time to warn for any attacks planned by the Germans. Graham Moore’s screenplay for the 2015 released “The Imitation Game,” by Norwegian director Mortem Tyldum, is not lacking in emotions. It entirely transports the viewer into the brilliant mind of the protagonist and jumps over and over again into different phases of the short life of the IT pioneer. Particularly emotional flashbacks depict young Alan’s troubling school days, characterized by bullying and isolation. But it was also the place where the young Englishman discovered his love for deciphering and met the only true love in his life, Christopher. Further scenes added to the screenplay depict Turing after the war when he had become a helpless and broken war hero, sentenced to two years of hormone therapy for homosexuality that ultimately turns him into a living wreck, and lets the audience suffer with him. For months Alan Turing tinkered with the machine, which should make it possible to decipher the Enigma every day. With agile care and overwhelming love, he continuously works on it, reminding him again and again of Christopher, even naming it after his school-love. Meanwhile, the codebreakers and colleagues of Turing in Bletchley Park rack their brains to decipher individual fragments of German communication. Every day without success, hundreds and thousands of families continue to lose their lives on the battlefield. The film unfolds the two emotional fronts better than any other historical movie I have seen. On one hand, the serenity and love that Turing puts into his work. On the other hand, the rush and pain resulting from the war outside of Turing’s isolation bubble. “The Imitation Game” shows the course of World War II from a perspective that hardly anyone knew of, that is, the war that Turing waged with himself. The way he almost unconsciously operated to understand the easiest human interaction and sexuality, just to become “normal.” But simultaneously the immense complexity and greatness of Turing’s mind leave no doubt as to why he was the one most qualified for this demanding task. Benedict Cumberbatch’s performance makes the viewer’s flesh creep for the full two hours. Emotion and cold-heartedness have never been so perfectly coordinated. Yet, they leave sufficient room for interpretation and reflection, making Alan Turing into something mystical while giving him the heroism and respect he earned with his actions. It gives us a bitter taste of how World War II directed events and, more importantly, how Turing dictated its outcome. The viewer experiences the success of Christopher with a racing heart. The type of staging and the initial failure of Turing’s invention allows the audience to participate and empathize with the action. At the end of the film, one feels a reasonable emptiness forcing a certain level of reflection. And only then does the viewer become aware of what Alan Turing has achieved in his far-too-short life, and the troubles he had to struggle with that no one should ever have to face. In the end, one can only guess what milestones this young person would have reached. The performance of Benedict Cumberbatch and the well-directed storyline conclude a history lesson that really strikes the viewer emotionally on so many different stages, and offers insights into World War II hardly anyone was aware even existed, even 70 years later.

With the support of Winston Churchill, Turing begins his project. Meanwhile, Joan Clarke, played by Keira Knightley, uses a hardly solvable crossword puzzle contest to secure a place in Turing’s workforce and, surprisingly, in his heart.