St. Louis history has been closely intertwined with American history since the founding of the city. But St. Louis is also connected with another, often overlooked, part of history, and that is the deadly practice of dueling, which often took place on a small strip of land in the middle of the Mississippi River.

Photo courtesy of Missouri History Museum

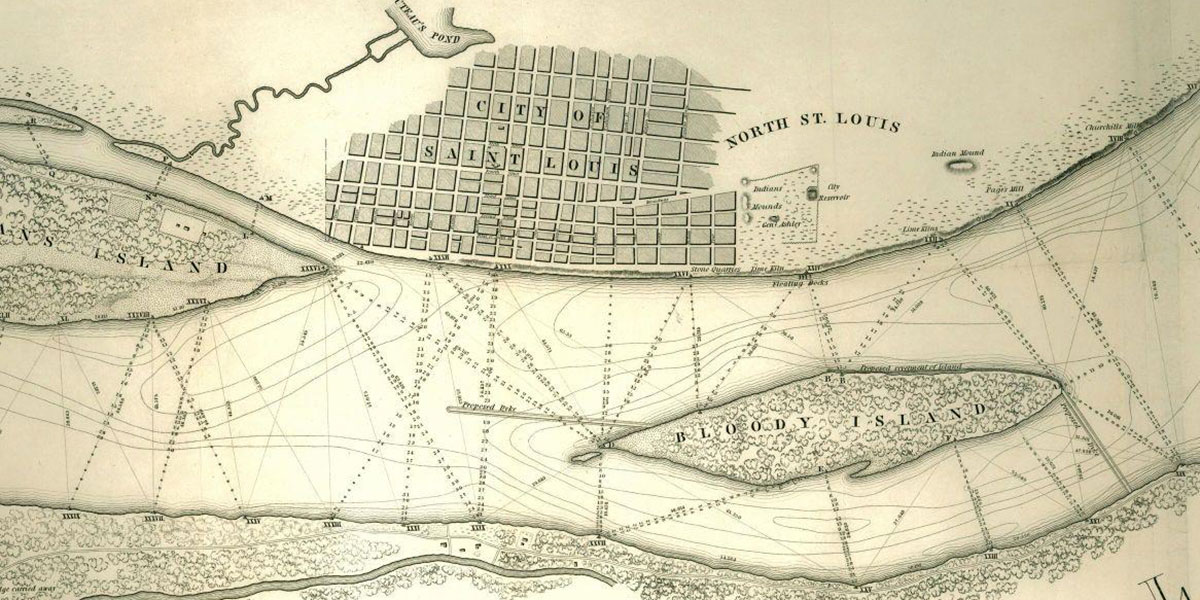

A map of the St. Louis riverfront and Mississippi River from 1837. Bloody Island is easily spotted as a prominent feature of the river at this time.

__________________________________________________

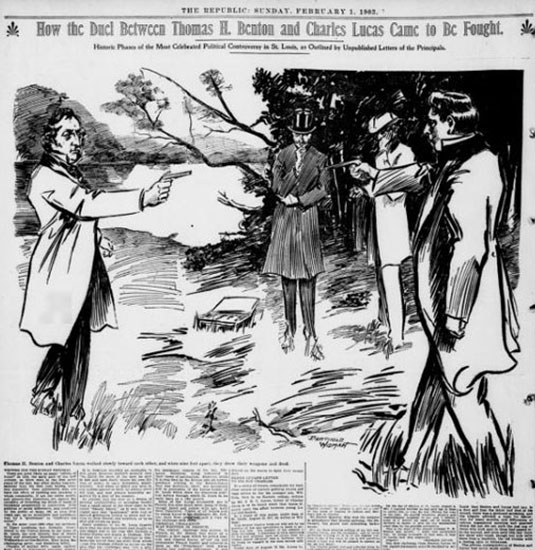

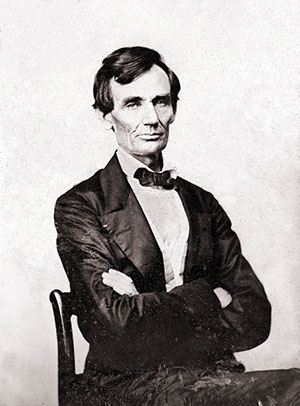

The city of St. Louis loves remembering and celebrating its role in early American history as one of the most important western cities and one of the last centers of civilization for those venturing further west. One iconic historic symbol of commerce and mobility St. Louis will always be tied to is the Mississippi River, one of the most important waterways in the country. The Mississippi River helped make St. Louis the city it is today, but one part of St. Louis and its mighty river history that seems to be forgotten almost entirely is the story of Bloody Island, an island-like sandbar in the river two centuries ago that was a popular local site for dueling and illegal activities. Andrew Wanko of the Missouri Historical Society pointed out the peculiarity of the history of Bloody Island: “It’s an interesting story of how the Mississippi River affected so many aspects of life in St. Louis, beyond the obvious trade and commerce connections we so often hear about.” The mystique of Bloody Island was well known at the time and not contained just to St. Louis or the surrounding areas. The island and sometimes-violent activities that happened there were notorious all across the country. “Bloody Island, in the midst of the rushing stream, stretches out its barren, sandy shores, and gloomy as the graveyard! ah! a graveyard! and when the associations connected with its dark history are permitted through the mind, the appellation is no misnomer. A graveyard!” This excerpt of an article, taken from an 1838 edition of the Iowa News, published in the then-Wisconsin Territory, shows just how intrigued writers and reporters were by the dangers of Bloody Island’s shores. The emergence of Bloody Island is interesting in and of itself, seemingly appearing out of nowhere in the middle of the river. “Bloody Island popped up in the middle of the Mississippi in the 1790s, as a result of the Mississippi’s current shifting and piling up silt and river debris,” said Wanko. “I find it so fascinating that this slow geographic change of the Mississippi could encourage such a weird cultural phenomenon in St. Louis.” This newly formed island was in the middle of the river, so the island quickly became a site of illegal activities and transactions because neither Missouri nor Illinois laws governed it. According to the Missouri History Museum, the island hosted everything from boxing matches to cockfights, but what makes the island so infamous and gave it the moniker, Bloody Island, were the numerous duels that took place there. The practice of dueling was an important part of early American history, with figures such as President Andrew Jackson famous for settling disputes of honor with the deadly system. If one person felt slighted or insulted by another they would issue a challenge, if the challenge was accepted then the challenged party would set the parameters for the duel, location, time, weapons, and distance in the case of guns being chosen. The two dueling parties would then meet at the assigned location along with witnesses and often a medical professional and they would then duel according to the set rules until one or both parties were dead or their honor was satisfied. Dueling in Illinois was illegal since it became a state in 1818 and Missouri outlawed the often-deadly practice in 1822, making the ungoverned neutral site Bloody Island attractive to those who wanted to settle their differences by shooting each other at close range. Duels continued to take place on the island through the 1850s, with many famous and high-profile combatants participating in them. The Illinois State Archives records a duel in 1817 between two lawyers, Thomas Benton of St. Louis and Charles Lucas of Normandy, Missouri, fueled by insults and an accusation by Lucas that Benton did not properly pay taxes. Both men would survive the first duel while sustaining injuries, Lucas had been shot in the throat and Benton in the knee, but when they returned to fight again, Lucas was not so lucky the second time around. The first duel had been held at a distance of 30 feet, the second was held at just 10 feet. Lucas’ shot missed and Benton shot him in the chest, killing him. Benton later became a United States senator for Missouri and served 30 years, from 1821-51, becoming the first senator to serve five terms. In August of 1831 Major Thomas Biddle, a veteran of the War of 1812, and Missouri Congressman Spencer Pettis dueled after exchanging insulting articles in the local newspaper. The Missouri State Archives chronicles their engagement: “As the challenged, the near-sighted Biddle chose the specified distance of five feet. The pistols were so close that both men received fatal wounds. Spencer Pettis died the next day and Major Thomas Biddle died on Monday.” Some of these clandestine duels actually drew crowds of spectators looking to watch the action. “A rumor has been afloat in this city that there was to be a bloody duel fought at bloody Island, near St. Louis, on the 9th inst. [meaning the ninth day of the current month]. The St. Louis Bulletin says that it was all a hoax. Lots of citizens, constables, &c. [sic] were on the ground however at the time appointed, but as the principals were absent no fun took place, and the crowd returned as wise as they went,” reported The Native American of Washington, D.C., on Dec. 30, 1837. However, the same newspaper had to print an addition to the above report of the duel, “… a meeting took place yesterday, a little before sundown, on Bloody Island, between Mr. Wm. C. Skinner and Mr. Wm. S. Messervy, of this city. … By this it would seem that the belligerents waited until the coast was clear of all spectators, when they went over and had the satisfaction of shooting at each other unseen and unmolested.” Multiple accounts of river boat captains settling disputes by dueling can also be found in the archives. “There was to have been an affair of honor on ‘Bloody Island,’ opposite St. Louis, on the 3d inst. [meaning the third day of the current month], between two steam boat pilots. They were to have fought rifles at 30 paces,” reads an article from the Liberty Advocate from May 19, 1838. “At the time the express slips of the St. Louis Commercial Bulletin were being despatched [sic] eastwards, a duel was going on between two river pilots, on Bloody Island, opposite that city,” reported the Morning Herald on April 10, 1838, all the way in New York. Perhaps the island’s most famous duel took place on Aug. 26, 1857, between Benjamin Gratz Brown and Thomas C. Reynolds. As stated in the Missouri State Archives, the two men, Brown, the editor of the St. Louis Democrat newspaper, and Reynolds, a United States district attorney, argued publicly over the issue of emancipation. Brown was a fierce supporter of emancipation while Reynolds was more supportive of local slave owners; this disagreement led to many scathing editorials being published in the Democrat. Brown was challenged by Reynolds, but Reynolds would not agree to Brown’s original terms, rifles at 80 paces. Eventually after another year of belittling each other in the public eye, Brown formally challenged Reynolds and the duel took place. Both men survived, Reynolds with no injuries, but Brown was shot in the leg and had a permanent limp for the rest of his life. The reason this duel is so famous is because both men went on to serve as governor of Missouri at different times, Reynolds in 1861 and Brown in 1871, and Brown eventually became a vice presidential candidate in 1872. However, this duel could have been easily overshadowed by a potential duel involving then-Illinois State Representative Abraham Lincoln. Lincoln was challenged to the duel by State Auditor James Shields, who said Lincoln had written a scathing article about him in the newspaper, the Sangamo Journal of Springfield, Illinois. Being the challenged party, Lincoln was allowed to set the rules, and he chose to fight with cavalry broadswords while standing on a thin wooden board. “I did not want to kill Shields, and felt sure that I could disarm him,” wrote Lincoln later in life. “Furthermore, I didn’t want the damned fellow to kill me, which I rather think he would have done if we had selected pistols.” Before the duel took place, both men were talked out of it by their seconds, chosen friends who would take the place of either of the duelists should one of them die, preventing what would have been one of America’s most famous duels from happening and possibly ending Lincoln’s life before he ascended to the presidency. Eventually the citizens of St. Louis became worried the island would continue to grow and cut off all of the city’s harbors. The Illinois Archives notes the United States Army Corps of Engineers sent a young officer to help with the problem. “Robert E. Lee, a young army officer at the time, disgusted with the official life of Washington, volunteered his services and came to St. Louis in 1837. Under Lee’s supervision two dykes were constructed in 1838,” according to the archives. Lee’s diversion of the river slowly but surely worked, and Bloody Island eventually was pushed against the Illinois side of the river, becoming a section of the mainland. Lee would go on to serve in the Mexican American War, leading the counter attack against John Brown at Harper’s Ferry, and eventually commanding the Army of Northern Virginia for the Confederacy during the Civil War. The section of the Illinois shoreline that Bloody Island ran into and then joined is still marked on many historic maps. Today it looks no different than the rest of the Illinois side of the river; train tracks run on top of it and there is no visible marker of what used to be the island. The island itself seems to be completely lost to history, much like many of the nefarious activities that took place there.

Photo by Jack Gienke

Photo by Jack Gienke

All that is left of Bloody Island. After the river was diverted in 1838 to help get rid of the island it was slowly pushed into the Illinois shoreline, eventually becoming a part of it.